The Oboe d’amore: Mission Impossible lll

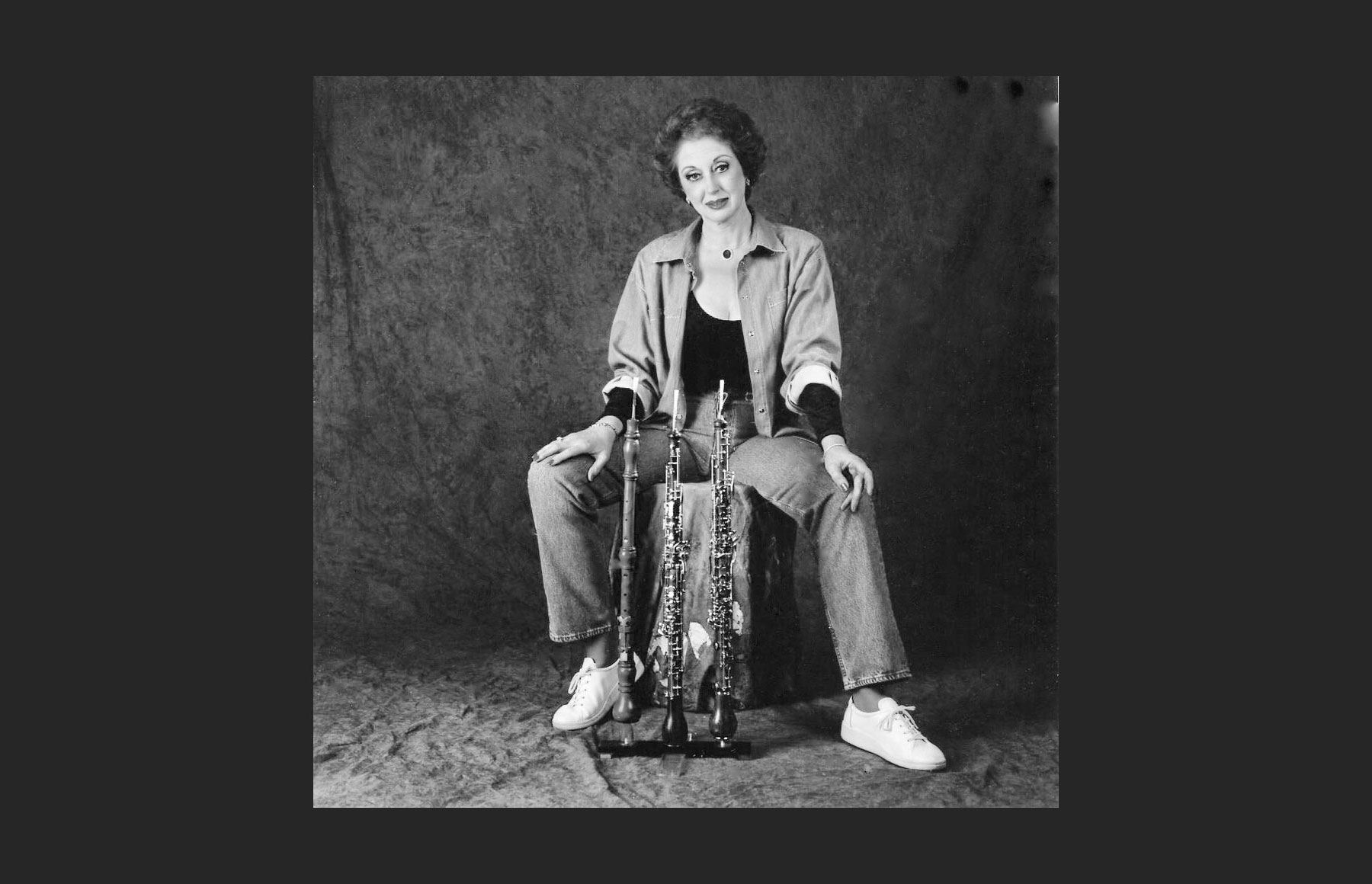

In this penultimate part of the guest blog series by Jennifer Paull, she guides us through more of her experiences with composers and her fascinating life in the music world.

In October 1971, the Shah of Iran hosted the most extravagant celebrations for the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great, in Persepolis. Immediately prior to this, in September, The Festival of the Arts Shiraz-Persepolis took place in the same location. Bruno Maderna, The Hague’s Residentie Orchestra and mezzo-soprano Cathy Berberian were to première his Festival-commissioned work ‘Austrahlung’. Maderna hadn’t fully completed the score and my job was to see to it that he burned the midnight oil until he had done – no computers in those days, copyists on standby!

Cathy introduced me to John Cage and Merce Cunningham who were there with Merce’s dance company. Stockhausen, too, was in attendance and I was to try to interest him in the proposed Granada TV biographical series of composer portraits. I networked considerably and was invited back to attend the next Festival, the following year. This time I was asked by the Iranian Ministry of Culture to coordinate their National Ballet Company’s visit to Sadler’s Wells. That went off well and I was subsequently entrusted with the organisation of the music for the official government film that had been made of the 2,500th celebrations. Orson Welles was in charge of the script and they needed someone to organise the music. In Teheran, I had been introduced to Loris Tjeknavorian by Farhad Mechkat, the Musical Director of the Teheran Symphony Orchestra, who had been with us in Persepolis. Loris, at that time, was virtually unknown outside certain restricted circles, although he was in charge of the Teheran Opera. He played me some of his unpublished piano music, which I was sure would be exactly what Basil Ramsey at Novello’s would like. He did and Loris came to London. His music for the son et lumière at Persepolis had won prizes and so he had been the natural choice for the film score. I booked the LPO to record the soundtrack, an orchestra in which I was unable to play as an oboist because I was a woman. “Don’t book me, I’ll book you.” That felt good!

By this time, Cathy Berberian had introduced me to Sylvano Bussotti and Luciano Berio, her ex-husband, who told me that I could play his Sequenza Vll on oboe d’amore. Bruno Maderna wanted to write a concerto for oboe d’amore as well as a theatre piece for Cathy (Voice) and myself (Oboe d’amore) together, rather along the lines of Stockhausen’s ‘Harlekin’. He saw us portraying two characters from the Commedia dell’arte.

These projects would have been the perfect way of getting my instrument beneath the 20th century spotlight I knew it so deserved. Very sadly, not long after this, Bruno was taken ill and died in 1973 before he was able to bring these plans to fruition.

Pretty shaken, I decided that I would move my focus back entirely to performance for a while. Composers would only keep on writing if I kept on performing, which is what I had promised in exchange for their work and I needed to concentrate on that. I moved to The Netherlands and freelanced, giving recitals wherever I could. There was plenty of opportunity to play and I recorded some of the pieces I had amassed for the radio, in Hilversum. A few years later, I moved to Switzerland where my family had been based since just before WWll. I put down roots, had four wonderful children and continued with my mission from my new permanent base.

More composers wrote for me and old friends added new works. Edwin Carr and Leonard Salzedo each composed six! Both of them had also written for what I decided to call an ‘Oboe Consort’ and I created my own group. This is a quartet of oboes to encompass the entire family from musette to bass. It really is a glorious sound! I was equally aware of the need for music for the other rare oboes, the musette and bass. I met Derek Bell, harpist of The Chieftains, bass oboe specialist and composer. He played bass oboe in my Amoris Consort and introduced me to composer friends of his. One, William Blezard, also wrote two pieces for me – and so the list continued to expand.

I was very much aware of how much I owed these friends who had given their time and talent to my mission. They knew full well that nobody would publish their works as compositions for oboe d’amore were far too narrow a specialist market to interest the big publishers. John McCabe’s ‘Dance Prelude’, published by Novello, includes a clarinet option uniquely to increase sales, not something he or I wanted. John Rushy-Smith’s ‘Monologue’ was published originally by Simrock (now Boosey & Hawkes) as an oboe piece, oboe d’amore being the alternative option! In reality that was the reverse, but these companies were based upon profit, which we all understood. The oboe repertoire has always been oboe first with some cor anglais very much second. I decided that I had to do something about that as well, so I started my own publishing house, Amoris International, to specialise in the oboe d’amore first and foremost! The other rare oboes and all of the oboe family of instruments would be represented as well and I would record as much of my repertoire as I could. I didn’t want to keep it for myself, it was for everybody to play so that the oboe d’amore would become part of every oboist’s standard equipment.

To be continued…